The central theme of this Substack, if it has one, is staying human while making films. Being a person connected to the real world. Not only because it feels morally necessary, not only because I don’t want to live any other way, not only because my heroes do — but because making art is interacting with the world. And if you’re disconnected from it, I’m not sure you’re making art.

The world right now is… well… so fucked. Difficult, complicated, sad, oppressive, overwhelmingly impossible to navigate — choose your adjective. It feels darker than it’s been in a generation. Whatever this phase of late-stage capitalism is, it’s not a hopeful one.

That’s got me thinking about the interplay between filmmaking and the world around us. (I’ll leave the question of what art can do to improve the world for another time. I believe it’s imperative, but I’ll need a better rallying cry than that).

This one’s about how we treat other humans. How do you leave a positive trail through the world with the work you’re doing, outside of the work itself?

How we create safe, creative spaces on set, in the edit, in the office. How a bit of psychology, a bit of empathy, and an awareness that there’s a bigger world beyond your film can change everything about how the work feels.

I’d like to think we’re beyond the stage where the talented, egotist arsehole is excused. But just in case we’re not, let’s kill that fucking myth straight away. If you can’t treat people decently, go and work in banking. There are plenty of other rapacious ways to earn money and get a sense of power by being abusive to other people. Keep it out of the arts.

For me, every single day at work should be a space where you’re trying to approach it joyfully. As a director, that tone comes from you. You are steering this ship. You don’t necessarily build it. You’re probably not even rowing. You might not know how the sails work. You’re plotting the course of this tortured metaphor. If you approach every day with a sense of joyfulness, that goes a long way. Read this article for a brilliant example of how the Daniels started each day on Everything Everywhere All at Once. What better way to create a vibe of creativity, equality and involvement on set? What better way to show vulnerability and make sure everyone’s pulling this way-overused ship metaphor in the right direction?

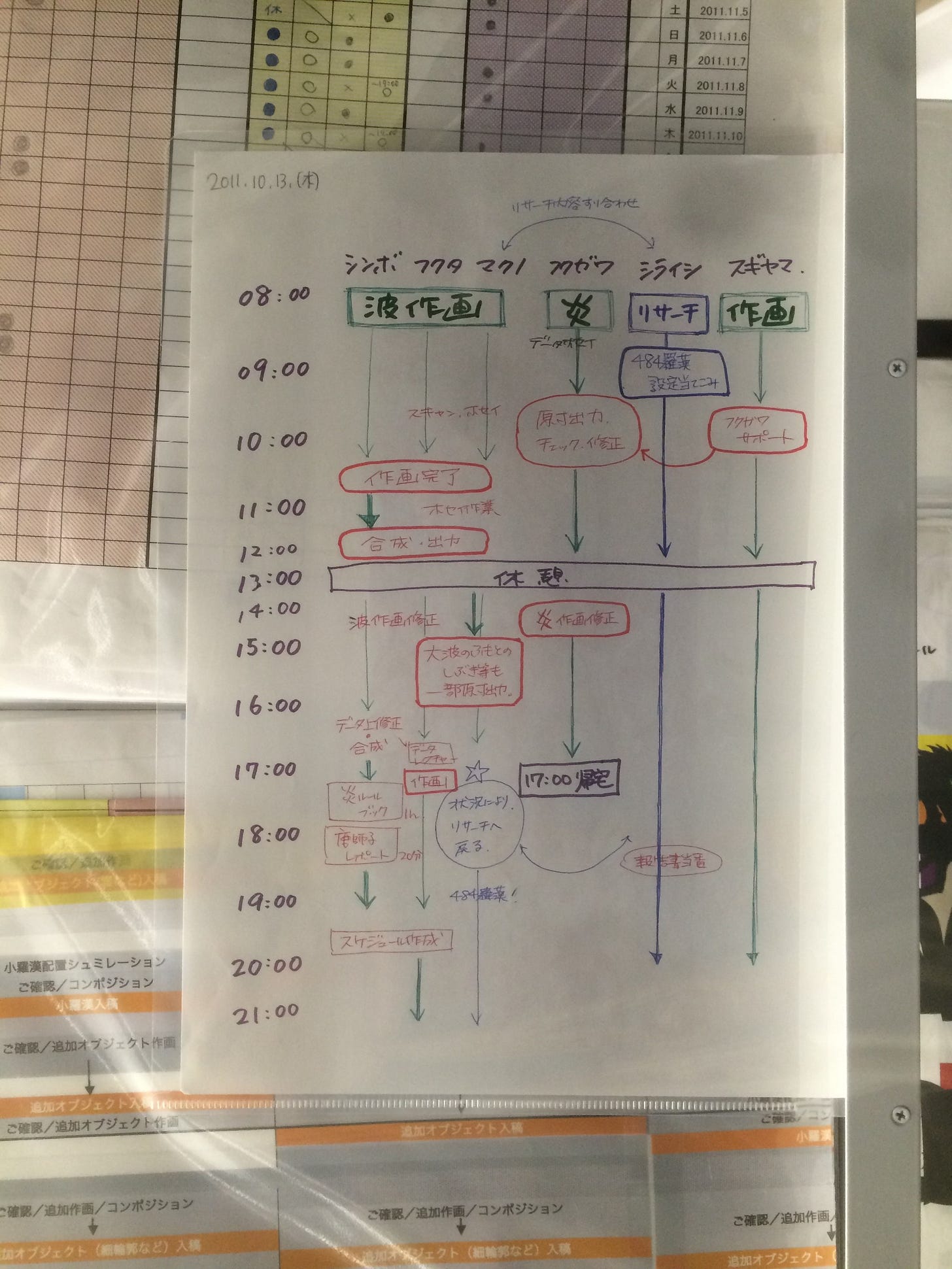

This isn’t forced. I love being on set. The first set I ever visited was a short film in the countryside near Exeter, England where I’m from, and I was instantly hooked. And I still find them utterly magical and unique every time. I even loiter around strangers’ sets if I stumble across them. Once in Tokyo, I got politely moved on after trying to peek at a sound recordist’s beautiful handwritten notes.

But the real world leaks into your set and your production, whether you like it or not. We need to be aware of it and of the impact it is having on each and every individual. There’s a lot of grief out there, there’s a lot of insecurity, there’s a lot to worry about. You need to hold everyone in a safe space without creating a barrier to the real world.

And this empathy isn’t just for ‘your’ people either, it should be for everyone you are interacting with. If one of your financiers or clients is scared about losing their job, you have two paths:

1. You can make it a confrontational exercise and battle for everything, or

2. You can make them feel like you’re caring for their livelihood with your work

That choice will define the atmosphere of your film far more than any lighting setup or lens decision ever could.

I made a film in San Quentin prison once. It was part of a sports anthology series of documentaries. The crew had just come off a very intense shoot in the desert with an extreme athlete. They were expecting to just shoot, shoot, shoot - to run and gun a lot. And they were nervous about heading into prison.

So instead of diving into shooting each morning, I had everyone sit in the van with me and I’d talk them through the emotion of the scenes we were going to shoot. I talked about how little I wanted, as long as it was the good stuff. And at the end of the day, I made time to do the same. It became incredibly calming, open and gave us time to get into deep conversations about what we were making and how we felt about it.

It changed the pace of how we were working and we started shooting in a tender, observed way - utterly patient and focused. We didn’t shoot crazy long hours, or loads of footage. But everything we got was really powerful.

And when we were set to go into the prison, I told them all that engaging with the people around them was equally as important as what we shot. If someone in the prison talked to us, we would talk with them, explaining what we were doing. It made us a trusted, respectful team within the yard, it took away the fear and it led to a special film.

Now I’m on a plane to a job where we’ve crewed up fast and I’ll meet most of my team for the first time on the tech scout. We’ll all have to adjust quickly, under pressure. So I’m thinking again about tone - how the way I talk, listen, and move through the day sets it.

I spend a lot of time thinking about the types of personalities I work with. I have a certain way of speaking. I have a certain way of listening. I like a certain volume and energy on set, and I want collaborators who mesh with that. I don’t want people who are exactly the same - I don’t want clones of me. I want people who are going to challenge me and question me and add different colors to this palette. But I want them to treat the world around them with the same empathetic awareness that I believe I do.

I’ve had it where someone I’m working for has had an incredibly shit day - for reasons completely separate from the film. Their kids might be sick. They could’ve had an argument at home, a dying parent, money worries, or just be overwhelmed by the world. As a director your set, your production has to be a place for them to be OK.

Because we are creating something that people love to have to go and sit in a dark room and connect with. That in itself is joyful. It can be emotionally taxing. Joy doesn’t mean no sadness. It doesn’t mean no heavy social drama. It can be deep. It can explode your horizons philosophically. It can make you weep like you’ve never wept before. But that deep, deep joy that I am talking about should come from creation. Should come from making something that will connect with other people in the world.

I like to think of the way Paul Thomas Anderson seems to carry himself nowadays, not the young angsty version but the one now who celebrates cinema and who seems to have a fucking good time making films and promoting them.

If we can create sets that have that same feeling, then aren’t we adding something back to the world as we go?

“Film is, to me, just unimportant. But people are very important.” — John Cassavetes***

*** big disclaimer - I don’t think film is unimportant, but it’s a good quote.

So much of this resonates with me and the film I'm working on. First the theme of empathy is baked into my film, a documentary on the personal stories of activists and why they do what they do. A common trait they have is more than just empathy, I've taken to calling it universal empathy. Caring about people you'll never meet, issues that may never effect you. I know I am a born empath. I'm trying to find answers in my film why some are born this way. I have 3 brothers. They are kind people but have never done what I have done my whole life. Activism, organizing and international development work. Can empathy be learned? Before we film an interview I have my crew read up and I give background on who we're interviewing. I already know the people we're interviewing but want them to be cognizant. Before filming I tell the interviewee that this is a safe space and if they need to pause or take a break just ask. We are very considerate to one another. Everyone really is committed and believes in the project and is very respectful. Typically we'll have a barbecue or go to a diner afterwards to relax and reflect.