Into the un-knowing.

The power of micro-encouragement and Turkish eggs.

The other day I got an email from a friend who is a very talented filmmaker. It was short but very lovely. And in it, there was a sentence that somehow balanced out months of waiting, redrafts of scripts, and failures to find funding.

My filmmaker friend wrote simply:

“I hope you write something about said child psychology.”

I’d been writing about my daughter changing schools, and how much of my time and headspace had gone into helping her through that.

I’m not quite sure why that line gave me such a jolt of confidence. Definitely partly because I trust this person’s point of view, and because I admire them as a filmmaker and as a person. But maybe also because having someone be excited to see what you do next is so incredibly exhilarating.

Thinking about that email, and basking in the glow of it, sent me into a whole loop about the power of being supported, of people being kind, and how much is still sitting in that, unrealised.

Because the onslaught of losing can be crap. We need to be lifting each other up, out of the shit. I can’t stand non-constructive comments.

When I was at university, just starting to make films, I sent a script I’d written to someone I thought was a good friend, who was also studying filmmaking. He sent back a load of notes that began:

“I’m going to come down pretty hard on this one.”

What the flipping fuck? What kind of arrogance do you need to start any email like that? Let alone to someone else starting out.

We don’t have to start singing Kumbaya, but if you can’t find the excitement and enthusiasm in something that someone has sent you, then what are you doing?

We should be praising the values we want more of, whether or not that particular film is to our taste. For me, that’s an essential part of giving notes on a script, an edit, or even just an idea. Your job is to be a cheerleader for what that person wants to make, to help them push it into the best version of that thing it can be.

It’s not to bend it to your taste, or make it more “accessible.” It’s encouraging that person to take it as far as they can. And the encouragement is a key part of this. Lord knows it’s fucking hard enough. And of course, real notes need real honesty. None of this means abandoning critical thinking. Good notes still require critique, rigour, and really looking at what’s working and what isn’t.

I take giving notes on other people’s scripts or films or works-in-progress very seriously. I read or watch more than once, and I’m always looking for the best in it and how to bring that best out.

There’s a moment in a podcast I loved where a filmmaker (maybe the Safdie’s - I can’t remember) talks about how they’d once been dismissive about another director’s film. Paul Thomas Anderson pulled them aside and said:

“Hey, what are you doing? We’re all in this together, we’re all trying to make things here.”

I thought that was really great. If we can support films that attempt to say something, mean something, do something emotionally, then more people will be encouraged to make films like that. We’re all in this together.

If this Substack had a subtitle, it would probably be about me searching for balance. Balance between all kinds of things. It’s only recently occurred to me that it’s about finding balance between what is hard in the film world - what is hard about making films - and the unbelievable, constantly regenerating inspiration I get from it.

I don’t want to turn this work I love into something that feels like an office job. Which means getting away from the computer as often as I can.

I’m consciously trying to reintroduce a more physical aspect into my research and practice. I think I’m becoming snow-blind from reading online, and it’s making me less spontaneous. My choices start to feel like how, on Spotify, I end up playing Hot Chip too much, whereas when I choose a record, there’s intention and variety around me.

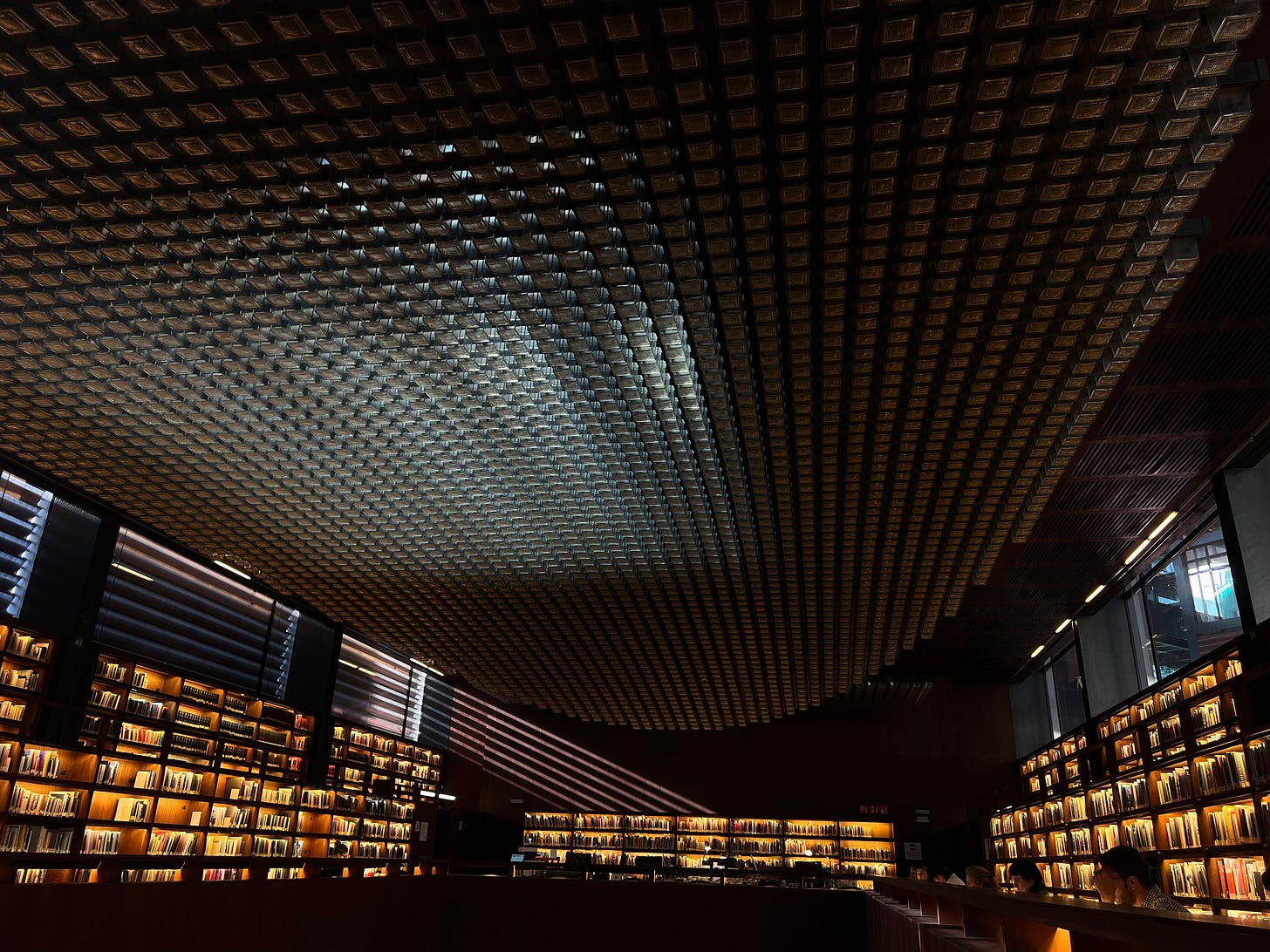

So I’ve been taking myself to bookshops, libraries, museums, galleries - not to search for anything specific, but to be around stimuli I can’t predict or control. Things that might lead to fresh ideas. Things that light my imagination.

I’ve also put blocks on most of the things I enjoy wasting time on with my phone (Substack, Instagram, The Guardian, football apps, googling myself). I’ve blocked them for most of the day, so that when I sit down, I’m forced to actually sit down with my thoughts.

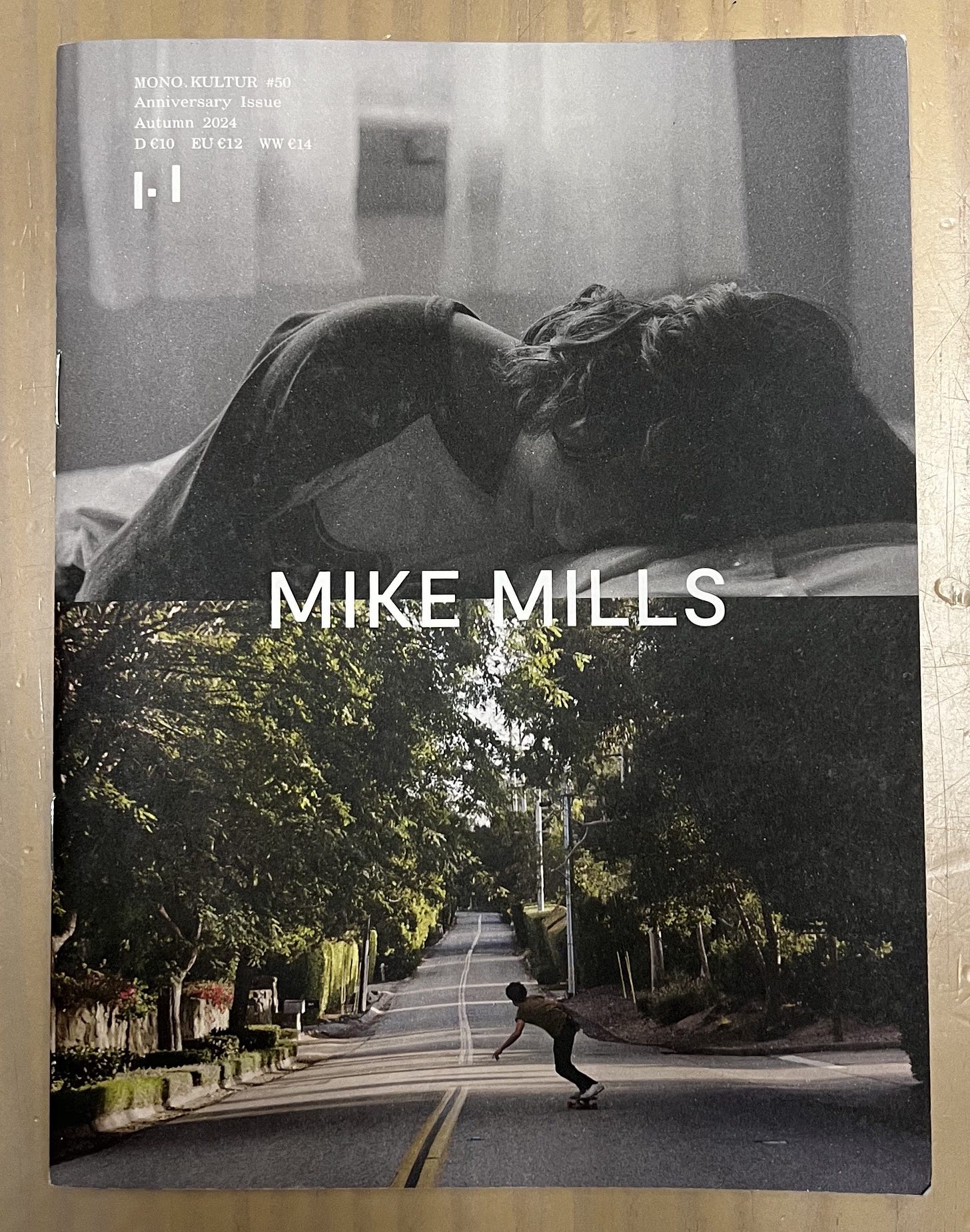

On one of these searches for physical inspiration I found a new bookshop. In it, I found the Kinfolk magazine I mentioned in my previous post, with an interview with Wim Wenders. I bought a book about topiary for a friend who’s doing a topiary project. And I found a small publication about Mike Mills.

And I took it to this library to read:

(Although I actually wrote this post after that library visit, eating a bowl of Turkish eggsand wondering if hot sauce and yoghurt might be the best combination if they need two things the humanity has achieved.)

The first third of the book is an interview between Mike Mills and Joachim Trier, and I don’t think I’ve ever read a film interview that resonated as deeply with me as these two talking.

For example:

But filmmaking is such a long process. When you’re writing, you show it to all these different people to see if you’re communicating the story you intended to, or what parts of your personal story are gripping and shareable. It’s a very interactive process. You have to do a lot of listening, a lot of testing, or trying it out. It’s a shared experience with a lot of failures. And then the editing, same thing, even more. I probably show the film to a group of 30 people, 10 to 15 times in the editing process. You get lots of feedback, and I encourage particularly negative feedback. Like, ‘Oh, that part didn’t work for you? Who else didn’t like that part and why? Let’s talk about that.’ And sometimes, afterwards, I just want to crawl in a hole from embarrassment and die a little bit. But you just keep going.

The interview really worked it’s way into my brain. Two of my favourite contemporary filmmakers, Mills and Trier. The questions they’re asking, the things they’re trying to balance and understand about their work, and their lives.

They talk about being human in ways that resonated incredibly deeply with me:

So there is never a sense of mastery. It’s more this willingness to throw yourself into that fucking pit of not knowing and an ability to endure that. That’s all it is. It’s certainly not mastery. And I think the willingness to endure all that, all these countless minor humiliations, like showing you a bad cut of my movie, or exposing my vulnerabilities to an audience of strangers - it’s like searching for a love that you didn’t get at home and you’re trying to get it with other people. And you need it so bad, you’re willing to endure all this, you know?

YES. Absolutely, Mike.

Incidentally heard Trier talk in San Sebastián and I’ve never been more impressed by a filmmaker. Not for how assured he was (nobody beats Christopher Nolan there—Nolan might be the most naturally intelligent-sounding person I’ve ever heard speak), but for how thoughtful, human, and genuinely engaged he was.

He seemed grateful for the audience’s perspective. His answers folded in being a parent, making films, working with talented people (Renate Reinsve was there and did a comedy bow), and the magic of cinema.

Actually, that doesn’t sound incidental at all. It sounds fundamental.

His whole interview with Mills, the whole tone, was right in my sweet spot. For example:

I have a love/hate relationship with that process because it’s so painful, but maybe it’s the most mature, interesting thing I’ve done in my career: subjecting myself to that and dealing with it.

What I really loved about the Mills/Trier conversation is that they don’t pretend to have mastered any of it. They keep throwing themselves into that pit of not knowing, over and over, and they find the courage to show unfinished edits and half-formed ideas because they’re still in love with the possibility of what a film can do, and because there are people around them who help them keep going.

Which brings me back to that one-line email from my friend:

“I hope you write something about said child psychology.”

It’s such a small sentence, but it’s exactly the kind of support that makes it possible to dive fully into writing another film. She’s saying ‘I’m interested in how you see this’ and ‘I want to read what you make of it’.

It doesn’t fix the days of despair lost in drafts, or the lack of funding (or the abundance of doubt), but it makes the whole thing feel possible.

If this Substack has a purpose, maybe it’s that: trying to practice that same generosity. Being honest about how hard and ridiculous and humiliating filmmaking can be, while also pointing to the things that make it worth it. The good notes, the thoughtful conversations, the strange books you find on a walk, the filmmakers who remind you we’re all in it together.

And if I can occasionally do for someone else what that email did for me - give them a little jolt of confidence, a reason to keep going - then all these words, and all these bowls of Turkish eggs, will have been well spent.

Yes, brother. To all of this ❤️

Yes Tomas! So much resonating here. Especially as I am still deep in the un-knowing and that your notes have been so encouraging and helpful through that. It makes me think about time, and how the lack of it turns that very necessary un-knowing into something riddled with pressure and anxiety. I’m currently at the point where the words “story” and “deadline” are making me never want to work professionally in film again. Or certainly not in a traditional “production”—which I suppose would make me (traditionally) unemployable. But as you say, the battle is to stay in touch with that feeling of potential, which is so exhilarating in filmmaking. So thanks for writing this to remind me!